The Hungarian Kingdom

ZoOm Hungary

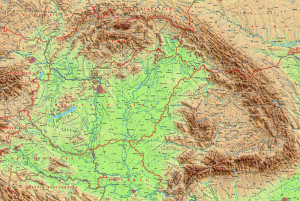

The Magyars have been living for centuries near the mouth of the Don, as vassals of the Khazars. From 889 they spend a few years in the Balkans in the service of the Byzantine emperor, but soon they move on to the northwest, through the Carpathian mountains. Since 890 their leader had been Arpad.

Arpad was elected prince by the chieftains of the seven Magyar tribes. His people numbered no more than 25 000, but together they subdue (within the space of a few years) the scattered population of the region now known as Hungary in 896 AD. So Arpad became the founder of a nation which somehow – in all the upheavals of central Europe – retained its identity and its language down through the centuries.

For several decades, the Hungarians had been a profoundly disruptive force in the region, constantly raiding west into Germany and south into Italy. They were eventually subdued when the emperor Otto I defeated them near Augsburg, in 955. After their defeat on the Lechfeld the pagan Hungarians adopted a more conciliatory approach to their western neighbors in Germany. In 973 the supreme chieftain Geza, great-grandson of Arpad, sent an ambassador to the German emperor Otto II. And two years later Geza and his family were baptized in the Roman Catholic church. Hungary settled down as the eastern bulwark of feudal Europe. In the next generation it had a king rather than a chieftain: Geza's son, Stephen I, succeeded him in 997.

Stephen I and the Arpad Dynasty: AD 997–1301

In his long reign Stephen transformed Hungary from a cattle-breeding, tribal and largely pagan community to an agricultural, feudal and Christian state. In doing so he acquired great prestige as a Christian ruler. The Crown of St. Stephen became a powerful symbol of nationhood. Stephen's canonization in 1083 testified to his stature among his contemporaries. For the best part of three centuries the descendants of Arpad maintained Hungary as a powerful Magyar kingdom. An important extension to Hungarian territory was the acquisition of Croatia. Kalman, the king of Hungary, invaded Croatia in 1097 after having been encouraged to do so by the pope. In 1102 he was accepted as the Croatian king. He pledged that the two kingdoms would remain separate, linked only by the crown of St Stephen. It was a union which lasted, in varying forms, until 1918.

In the spring of 1241, the first sentries of dreaded Mongol forces appeared at the north and north-eastern passes of the Carpathians. They came to grips with the main Magyar forces, led by Bela IV, in the valley of the river Sajo. During the night, the Tartars secretly crossed the river and set fire to the Magyar camp. The greatest part of the besieged Magyar army, suffering an attack from the rear, was annihilated. In fact, it did appear as though Hungary had been annihilated by the Mongol invasion. But internal dynastic conflicts erupted within the Mongol Empire, resulting in the withdrawal of the Mongol hordes from the country in the summer of 1242.

Bela IV began the reconstruction of the country, building castles and fortified towns to forestall the threat of another Mongol invasion. He invited German, Walloon and Italian settlers, and by granting them special privileges, promoted urban development. The king, who was called ‘the second founder of the state’, ordered the construction of Buda Castle. The king, fearing another Mongol invasion, encouraged feudal lords to build strongholds. The stormy and glorious reign of Bela IV (1235–1270) was followed be renewed struggles over succession and battles between opposing factions. Later, with the death of king Andrew III, the male line of the House of Arpad became extinct.